With Remembrance Sunday this weekend carrying the additional significance of the 100-year anniversary of the end of World War One, Rob Cole reflects on the first ever meeting between Wales and Australia just a few years before the start of global conflict...

With Remembrance Sunday this weekend carrying the additional significance of the 100-year anniversary of the end of World War One, Rob Cole reflects on the first ever meeting between Wales and Australia just a few years before the start of global conflict…

We are all aware of the remarkable young men who have featured in the recent Wales v Australia battles. Alun Wyn Jones, Jonathan Davies and Leigh Halfpenny will be on parade for the home side today, while the Wallabies will have David Pocock, Will Genia and Israel Folau in their ranks.

Go back a few years and the fixture has been graced by the likes of Sam Warburton, Gethin Jenkins, Shane Williams and Mike Phillips in red, John Eales, George Gregan, Matt Giteau and George Smith in gold. True greats of their era and players who were global stars and household names.

But if you head back 110 years to the first encounter between the two teams in Cardiff on 12 December, 1908, you will discover some equally remarkable men who not only served their country on the field of play, but also off it. The mists of time may have clouded their memory, but many of them left an indelible mark through their actions both on and off the field.

Pride of place on this weekend of all weekends, as the world prepares to mark the 100th anniversary of the ending of World War 1 on the 11th hour of the 11th day of November, 1918, has to go to the Welsh duo of Johnny Williams and Phil Waller. They paid the ultimate price for serving King and Country and were among 13 Welsh internationals who lost their lives in the global conflict. The Australians lost 10 of their internationals.

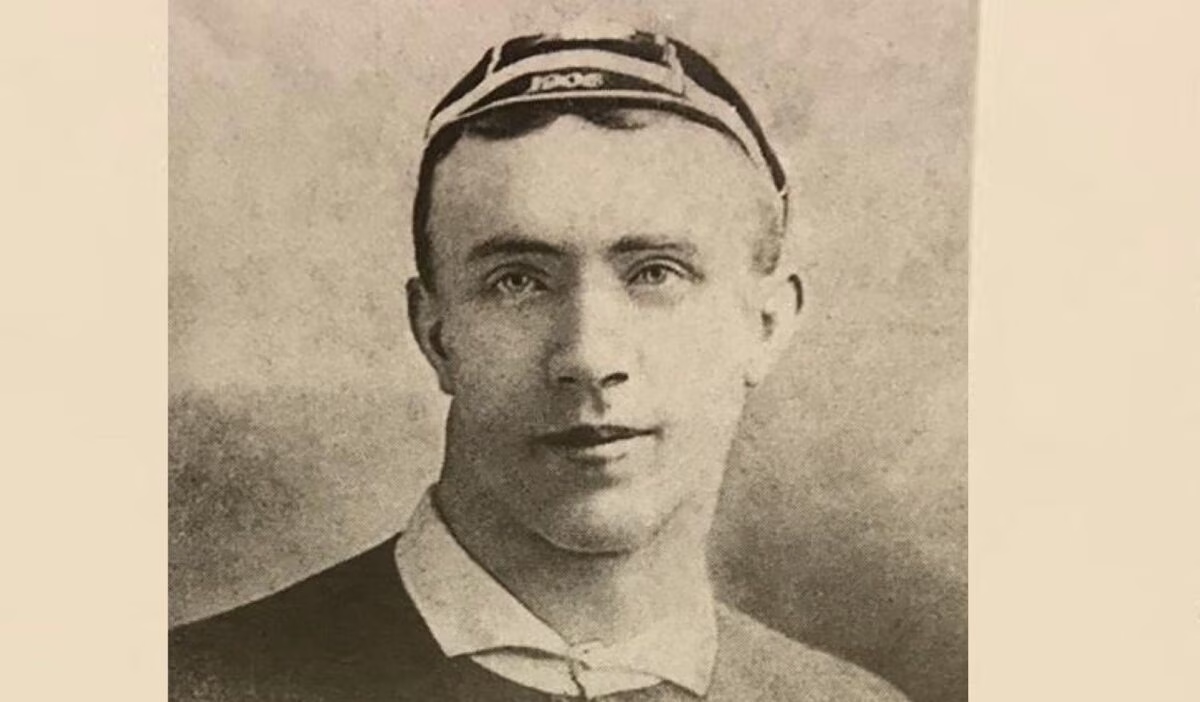

Williams, who was the second of three Welsh internationals to be killed in France in July, 1916 – Dick Thomas at Mametz on 7 July, Williams on 12 July also at Mametz and Dai Watts two days later at Bazentin – was the Ieuan Evans or Shane Williams of his era. He scored a record 17 tries in his 17 Welsh appearances, surpassing the previous best of 16 scored by Willie Llewellyn. However, less than a fortnight after reaching 17 tries in February, 1911, he had to share the record with his fellow Cardiff wing Reggie Gibbs when he joined him on the same total.

Their joint record remained intact until 19 December, 1953, when Ken Jones joined them with his famous try in the win over New Zealand. Gareth Edwards then finally overtook them with his 18th try in the win over Ireland in Dublin in 1976 – a week short of 65 years later!

Williams also went on the 1908 British & Irish Lions tour to Australia, top scoring with 12 tries in 20 appearances, including two Tests, in New Zealand and Australia. He played through three Triple Crown and Grand Slam campaigns in 1908, 09 and 11 and lost only twice in a Welsh shirt.

That was a good enough record to earn him a place in the World Rugby Hall of Fame in 2015, a posthumous inductee along with one of his opponents in the 1908 clash with Australia, Tom Richards. ‘Rusty’ Richards not only played for Australia, but also for the Lions on their 1910 tour to South Africa.

One of his team mates on that trip was Newport forward Waller, who made his debut as a teenager against the Wallabies. Like Williams, he perished in France, killed by a stray shell as he was driving away from the front to go home for some much needed leave. He had been on the winning side in each of his six successive internationals, including a Triple Crown and Grand Slam in 1909.

A number of other players from both teams also served during WW1, with Richards being awarded a Military Cross for his efforts. Although twice wounded, he led a raid at Bullecourt in 1917 that earned him this citation for his MC:

“For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. He was in charge of a bombing party and despite strenuous opposition succeeded in extending the line 250 yards and holding a strong post. He set a splendid example throughout.”

By the time the Wallabies arrived in Wales they had already been crowned Olympic champions after beating Cornwall, the English county champions, in a one-off final for the gold medal. Wales had been written to by The Reverend Robert de Courcy Laffan, Hon. Secretary of the British Olympic Council and British Representative on the International Olympic Committee, in 1907 to ask if they would play in the tournament, but they merely referred him to the International Board.

The Wallabies won 32-3 at White City Stadium and 47 days later Wales beat the Olympic champions 9-6 at the Arms Park. Not content with one Olympic gold medal, the Wallaby wing Daniel Carroll, picked up another as part of the USA team that triumphed at the 1920 Games. Carroll had stayed on in America to study after the 1912 Wallaby tour there and was player-coach of the victorious team in France. Carroll had served with the US Infantry in France during WW1 and was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Chris McKivat, John Barnett, Bob Craig, Jack Hickey and Charles Russell all returned to Wales with the 1911-12 rugby league Kangaroos, gaining a 28-20 revenge victory over the Welsh national side at Ebbw Vale.

The Welsh win over the Wallabies was their sixth in a row, a number matched by their counterparts of 2018 with last weekend’s 21-10 victory over Scotland in the opening game of the Under Armour Series. Billy Trew’s team went on to notch 11 straight wins between 9 March, 1907, and 1 January, 1910 – a record that has never been broken by another Welsh team.

Trew was another triple Grand Slammer, along with Dicky Owen and Tom Evans, and one of the greatest of all Welsh captains. When he died in 1926, the streets of Swansea were lined with mourners looking to pay their last respects.

The Welsh full back that day was Bert Winfield, who completed a hat-trick of southern hemisphere scalps having played in the 1905 win over New Zealand and the 1906 triumph by Cardiff over the Springboks. He served in the 16th Battalion (City of Cardiff) of the Welsh Regiment during WW1 an also played for Wales at golf.

The then Newport centre Jack Jones made his Wales debut against the Wallabies having already made three Test appearances for the 1908 Lions down under. He went on a second Lions with Waller and Richards in 1910 and made his final Welsh appearance in 1921.

WALES V AUSTRALIA – THE FIRST MEETING IN 1908

WALES 9 – 6 AUSTRALIA

Scorers:

Wales: Tries: Phil Hopkins, George Travers; Pen: Bert Winfield.

Australia: Tries: Tom Richards, Charles Richards

Wales: Bert Winfield; Johnny Williams, Jack Jones, Billy Trew (captain), Phil Hopkins; Dick Jones, Dicky Owen; James Watts, George Travers, George Hayward, Jim Webb, Phil Waller, Tom Evans, Ivor Morgan, David Thomas

Australia: Phil Carmichael; Charles Russell, Eddie Mandible, Jack Hickey, Dan Carroll; Ward Prentice, Chris McKivat; Jack Barnett, Tom Griffin, Charles Hammand, Albert Burge, Paddy McCue, Bob Craig, Tom Richards, Paddy Moran (captain)

Referee: Gil Evans (England)

THE FIRST WALLABY SKIPPER – HERBERT MORAN

Herbert Moran captained the Wallabies on their first tour and played his one and only international against Wales. He served as a Lieutenant in the Royal Army Medical Corp of the British Army during WW1.

He was sent to Gallipoli as a surgeon on a hospital ship, where he contracted amoebic dysentery. He went to Malta and was then sent to Mesopotamia as a Lieutenant at No. 23 Stationary Hospital, Indian Expeditionary Force.

Never one to suffer fools, this was his view of the conditions in which he had to work:

“This so called hospital carrier had been for 30 years in the cattle trade, had brought cattle to Mudros just recently, but there under the magic wand of a whitewash brush had been suddenly transformed into the travesty of a hospital ship. We herded them on mattresses laid down in what had once been stalls for cattle. For an operating theatre I used the dispensary in the centre, on which was a narrow fixed table. Our chief drug was rum and castor oil. Each man having his wounds dressed received a very liberal tot. If we could not offer them the sense of security which a real hospital ship would have given, at least we tried to make them happy with a mild intoxication. By Somathrace (Greek Island) we stopped to drop our dead. There were no flags in which to wrap them, nor any great ceremony, no padre was present to offer a blessing. In war the dead shame always those who survive.”

He also tried to rally recruits with an impassioned plea from the front in 1915 in a letter to newspapers in Australia:

“You must all come over if you want to win this war – ‘every man Jack’ of you. It is fighting all-in now, and the slacker and the shirker merit only a noose of rope. It is the only game worth playing at present, and they are in our twenty-five. We want all the young men, and the old men, too, to put it in with vigour. Send us men, men, men, and more men. It is the best game in history. There are no rules, and the only referee – posterity – has a whistle that cannot be heard. Yes, they’re in our twenty-five at present, but when we heel out our ammunition more cleanly we shall move forward. Meanwhile we want men – men with fierce, relentless eyes, and men with ruthless hands; men of the Anzac breed. There is no let-up and no begging pardon. If we lose we are out of the competition forever, and when we win we shall despise those who looked over the fence when our line was in danger.”